The New Friends of Eddie Coyle

Eddie Coyle’s new friends have gotten into real estate. Or, to put it more plain: there are days when it feels like Boston — if not most of the state of Massachusetts — has been captured by real estate interests, and no one has seemingly been able to do anything about it for years. (We’ve been talking about establishing just cause eviction protections in Boston — that is, tenants simply being told why they’re being evicted — for six years, for instance.) What makes this problem worse is the degree to which people simply don’t seem to care, the degree to which people don’t organize, the degree to which people think things are fine, the degree to those who tell the story of Boston outside of Boston still think the city is stuck in 1970, the degree to which those inside Boston still carry a Dropkick Murphy’s-like idea of the city around with them, and how I’ll bet you dollars to Dunkin’ Doughnuts that everyone will inevitably grouse about how things ‘used to be’ twenty years hence.

I grew up in Medford, Massachusetts in the 90’s. I was an undergraduate in Boston during George W. Bush’s second term. By 2001, Boston was a minority-majority city. From a ground perspective, it was (and had been) obvious. I’m not necessarily offering this up because I believe my story is the story to best explain development and displacement across the Boston Metro area, but because — even with all the places I’ve been and haven’t been — I’ve managed to keep an eye on the same story for twenty years, and even I’ve noticed a change.

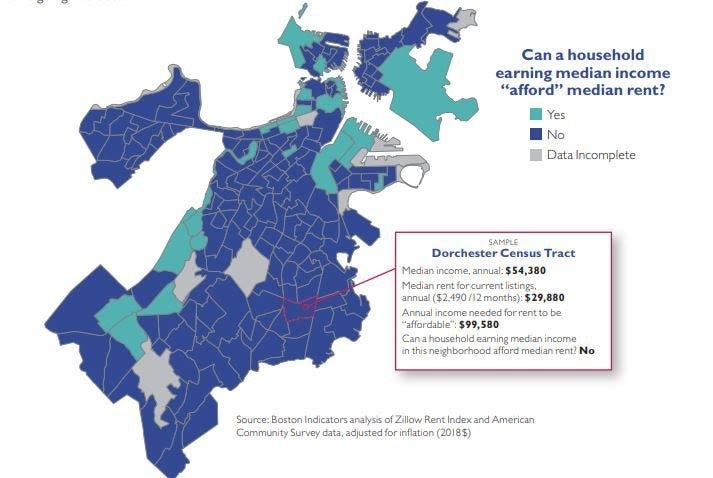

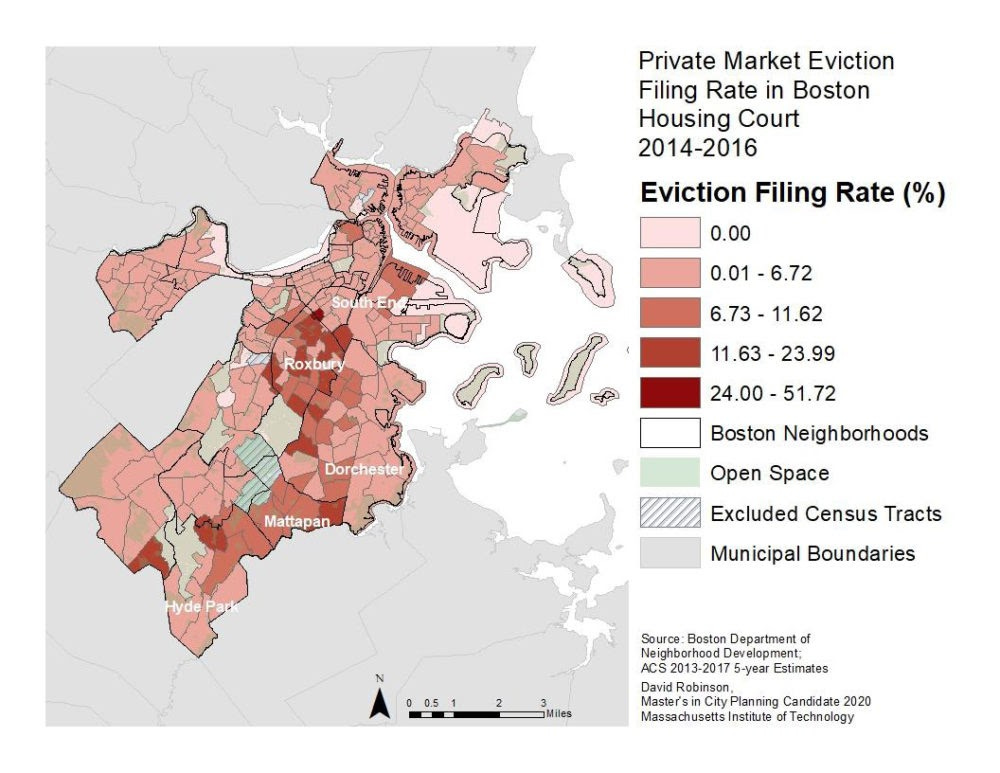

Here’s where that story currently stands: as of 2018, 88% of renters in the Boston metro area couldn’t afford their neighborhood’s median rent. (The first chart on top, with the deep blue representing the inability to pay.) The city needs to build 15,000 homes every year in order to keep track with population growth. (It has never hit that threshold.) Rent is currently among the highest in the nation outside of New York City, San Francisco, and San Jose. The average median net worth for African-Americans in the city is $8. And, as Elliot Schmiedl noted in a blog post over at Massachusetts Housing Partnership, the financial burden for African-American families doesn’t just end there: “... five cities accounted for 45.7 percent of all loans to black borrowers in Massachusetts in 2017. Black borrowers received no home-purchase loans in 129 of the state’s 351 cities and towns and only a single loan in 50 communities.” As the report “Towering Excess” notes: “In 2015, not one single home mortgage loan was issued for African-American and Latino families in the Seaport District and the Fenway, two Boston neighborhoods with thousands of new luxury housing units.” Potential black renters are more likely to face discrimination, per a 2020 study run by Suffolk Law, with real estate agents showing half the number of apartments to Black renters they’d otherwise show to white renters between 2018 and 2019 (to say nothing of the difficulty faced by those with Section 8 vouchers.) And despite the shared unaffordability of living in metro Boston — despite how hard communities of color in particular were hit by the 2008 crash nationwide — the rate of evictions are happening in metro Boston at a scale ten times greater in communities of color than in predominantly white neighborhoods facing the same problem. (The red chart below.)

Defenders of this would say that Boston isn’t allowed to run a budget deficit by law, gets 70% of its budget from property tax, and can’t raise its property tax over 2.5%, which means that — if you want to increase the city budget; if you want to have more money to do more things for more people — then one way to go about doing it is to set up a system that greenlights one luxury development after the other.

But it’s also racist. And — as Samuel Stein reminds us in the book Capital City — in chasing after the fact that global real estate is worth $217 trillion and constitutes 60% of the world’s assets — “cities are incentivized to drive out anything that is understood to reduce property values: types of buildings, businesses, land uses or even people.”

What are some possible solutions for all this?

I’d be hesitant to offer beefing up the Inclusionary Development Policy as a solution for reasons that are perhaps best explained elsewhere. There’s a coalition working on addressing development and displacement as of this writing — including a bill that was just reported out of committee in the State House on October 1st, 2020 that extends an eviction moratorium, establishes a rent freeze, establishes just cause evictions, and provides renter’s assistance — but the effort needs to be larger. The effort needs to grow. The process of creating and maintaining affordable housing is so vulnerable to capture by moneyed interests at so many different points of the process that I know that part of me won’t be satisfied until every homeless person in Copley Plaza, North Station, and South Station gets to live in One Dalton for free, especially if certain Twitter screencaps are to be believed.

One reason these kinds of fair housing efforts need to go bigger is because of all the other projects that are underway or are coming: Doyle’s Cafe is going to reopen as part of a ‘condo complex.’ Samuels and Associates are set to build a $700 million office and hotel complex over the Mass Pike. Another developer is proposing another massive project at Columbia Point — as if the traffic circle over there wasn’t enough of a nightmare already. A Houston-based developer is throwing a tower on top of South Station. Of the 2,000 units built or under construction in Revere, there’s only one new building with some 50-some units that’s for those with low income. The BPDA gave the go-ahead to a huge project in Dorchester last year even after acknowledging that residents ‘had a point’ about displacement in the area. After a company suggested that it was going to change the tower it was building in the Financial District that would result in $22 million going to the city’s affordable housing fund instead of the initially agreed upon $48 million, some of which would have gone to affordable housing in Chinatown, the BPDA approved the change regardless.

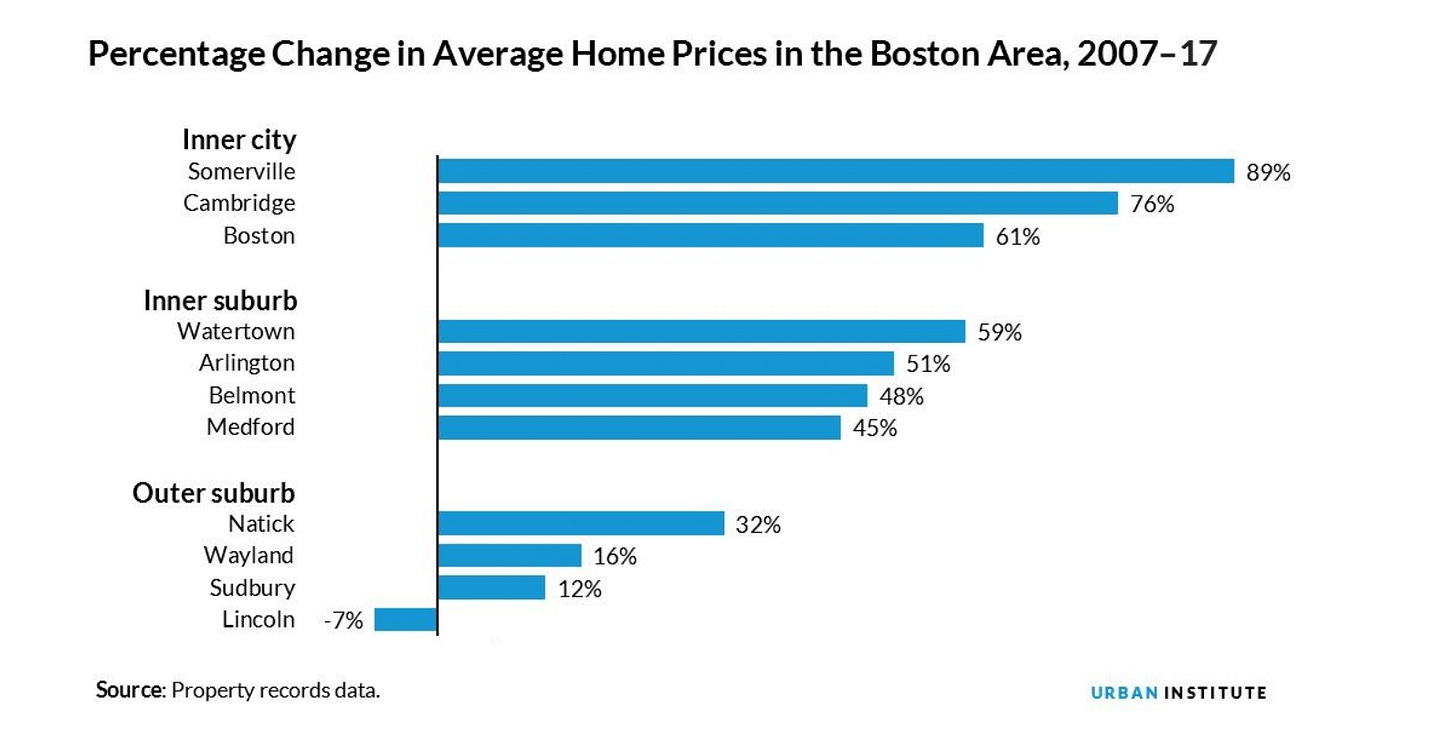

And that’s just a part of it. And this is to say nothing of the debacle that was Seaport, nor the change in housing prices we’ve seen since 2007.

It’s a lot. It’s the kind of thing you want to find a way to get under control in a comprehensive way.

One idea as to how to do this is to simply dissolve the BPDA. No more Robert Moses by committee.

Another way to tackle this was advanced by Lisbon City Council in Portugal at the end of July, and it’s converting Airbnb units into affordable housing, which could kill two birds with one stone: Boston needs affordable housing — 17,000 people are on the affordable housing waiting list for Allston-Brighton — and studies have flagged Airbnb’s role in hiking rents and accelerating gentrification.

A third idea stems from the recent victory gained by Philadelphia Housing Activists, who — after six months of direct action — managed to get the city to transfer 50 vacant homes to a community land trust that will aim to hand these homes over to those making less than $28,000 per year.

But ideas without the ability to implement them are just ideas. And, without a critical mass of the community pushing for these ideas, we have to turn to the role of leadership.

As depicted in the Frederick Wiseman documentary City Hall, Marty Walsh comes across as a nice enough man who’s perhaps a little ‘too’ interested in boards and commissions. But boards and commissions also tend to prioritize those who know how to access boards and commissions. (Consider how the BPDA recently announced who some of the new business tenants at Suffolk Downs would be without ever opening the process up to application. Everyday folk were just given a fait accompli.) A 2009 Boston Globe poll said that 57% of the city’s residents had met former mayor Tom Menino — and he still had five more years left in office after that poll was taken — and I can’t shake the feeling amidst all these events that there’s a level of efficacy in running a city that can still be wielded by having a deeply personal sense of the city. By showing up. And there are days when I’m not convinced the other guy has it.

This piece has been edited. More soon.